Annie Kwai’s book Solomon Islanders in World War 2: An Indigenous Perspective, brings indigenous wartime contributions and experiences to the forefront. It is the first book of its kind to be written by a Solomon Islander from their own perspective. Most historical books about the battle of Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, have been written by Australians or Americans.

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor was the catalyst for the United States’ entry into World War II. In the Pacific, the Solomon Islands — particularly Guadalcanal — became the centre of fierce fighting between the Japanese and the United States. The contributions that the Solomon Islanders, who served as coast waters, scouts and labourers made to the war effort are often forgotten in popular discussions.

Prior to WWII, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) had put a coast-watching network in place in the Solomons, as an intelligence gathering platform that used civilians with radios to report any suspicious development in their assigned areas. The Coastwatchers’ work was so significant in winning the Solomons Campaign that US Admiral William Halsey, commander of the South Pacific Area, said that, “the Coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal and Guadalcanal saved the Pacific.”

Does the description of the Islanders as ‘loyal’ to the allied cause oversimplify Islanders’ participation in the war?

The success story of the Coastwatchers has been celebrated extensively. Numerous books have been written about how brave the Coastwatchers were and how significant their work was to the Allied victory in the Solomons Campaign. But details of the foundation of this success – the role played by local Solomon Islanders – have been under-reported and sim- plified. The 23 Coastwatchers in the Solomons archipelago (including Bougainville) relied heavily on the support of the local people. This widespread support is often referred to as simply “loyalty.”

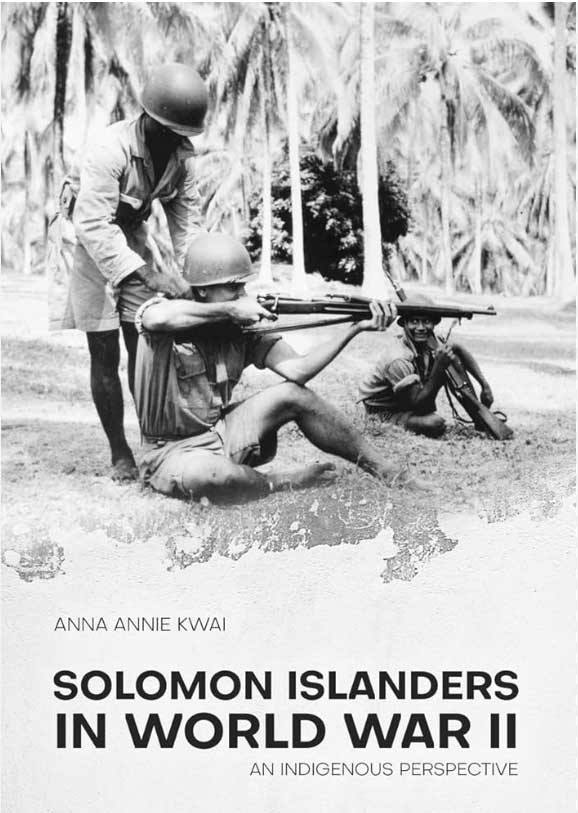

Solomon Islanders in World War II: An Indigenous Perspective

Authored by: Anna Annie Kwai (ANU Press, 2017)

Can you describe some of the divergent motivations for Islanders to contribute to the war effort?

Indigenous wartime involvement was inspired by various factors, some pushing through perceived duty or responsibility and some pulling through attraction. There was a sense of familiarity and obligation toward the longstanding British colonial administration, so despite Japanese propaganda casting themselves as anti-colonial liberators, when Japanese troops invaded the Solomons they were immediately regarded as outsiders and “enemies.” But the war was also a very new and exciting event that fuelled the curiosity of local men and prompted them to take part. The easy abundance of food in labour camps at Lunga and elsewhere was another draw, and the attraction of paid wages lured many men from their villages. There was also a sense of prestige attained from joining ranks with the Allied soldiers and sailors as fellow warriors.

But there were more coercive factors that drove local par- ticipation that shouldn’t be ignored. Some Coastwatchers imposed harsh punishments upon mere suspicion of any sympathy for or collaboration with Japanese troops. This at times included casual behaviour by Islanders that was interpreted as suspicious. Punishments imposed by some Coastwatchers included severe beatings unrealistic for the “crime” committed. This was done with the intention to instil fear in the minds of locals, in order to deter contact of any sort with Japanese troops.

Prior to the war, the colonial government was headquartered on the small island of Tulagi. Upon the Japanese invasion it was moved out of harm’s way, to Auki on Malaita. As soon as American forces landed on the island of Guadalcanal on August 7, 1942, the government moved to Lunga. Despite controversy, the post-war administration moved to Honiara (on Guadalcanal) where the capital city is currently located. This was to take advantage of war infrastructure, including Henderson Field (now the international airport), roads, and structures that were readily available. The placement of the capital on Guadalcanal planted the seeds for much of the problems that would eventually erupt into the “Tensions’’ of 1998-2002.

The war itself was an eyeopener for Islanders. It provided Islanders with the opportunity to interact with soldiers of different nationalities and race on a personal level that was not possible under the colonial administration. This made Islanders question their experiences and encounters with white members of the colonial government. For the first time Is- landers were able to drive the same machines that white men drove, share the same food that white soldiers had, and feel a certain degree of empowerment. This exposure aggravated Islanders’ grievances of inequality experienced under the colonial administration. So even during the war, Islanders began to protest for an increase in their wages. From these feelings of inequality and injustice the famous socio-political movement Ma’asina Rule was formed. In the aftermath of the war, the fight for equality and recognition shifted to a fight for political autonomy from Great Britain, and 33 years after the war ended, the Solomon Islands finally gained independence (in 1978).

In the Solomon Islands today, how is the war commemorated? What is the linkage between Islanders’ war memorials and nation-building?

War commemoration in the Solomon Islands has only recently shifted in focus to the remembrance of local participation in the war. Observances have always been the affair of the Americans or the Japanese, but recently the recognition of local involvement in the war was brought into annual commemorative events. This is because there is now more public awareness and education on the roles of Solomon Islanders during the war. Monument building is part of this awareness, and is a significant symbol of unity within a broader contem- porary Solomon Islands society. This sense of unity was initiated by our ancestors during the difficult times of the war and grew throughout the journey to political independence. It is one of the pillars of our patriotism to our country. Islanders’ war memorials, in this regard, are symbolic of a unified sense of nationhood, and gratitude to those who laid the foundation for Solomon Islands sovereignty.